Natural History Features Along the William O. Douglas Heritage Trail: Yakima to Mount Rainier

The William O. Douglas Trail is an 80-mile recreational pathway, honoring the conservation, historic, and cultural legacy of the late William O. Douglas, U.S. Supreme Court Justice. It begins in Yakima, Washington and climbs the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains to their crest, and then descends down the west slopes ending in Mt. Rainier National Park.

The William O. Douglas Trail region’s fascinating cultural history and its recreational attributes were chronicled in many of the books written by Justice Douglas. He also celebrated the extraordinary natural wonders of the region. The William O. Douglas Trail follows a route showcasing these natural attributes. Moreover, as the trail is set in the heart of the rugged Cascade Mountains, world renowned for these scenic wonders, much of the heart of which is now protected, through actions of visionaries such as Justice Douglas, in national park or wilderness status.

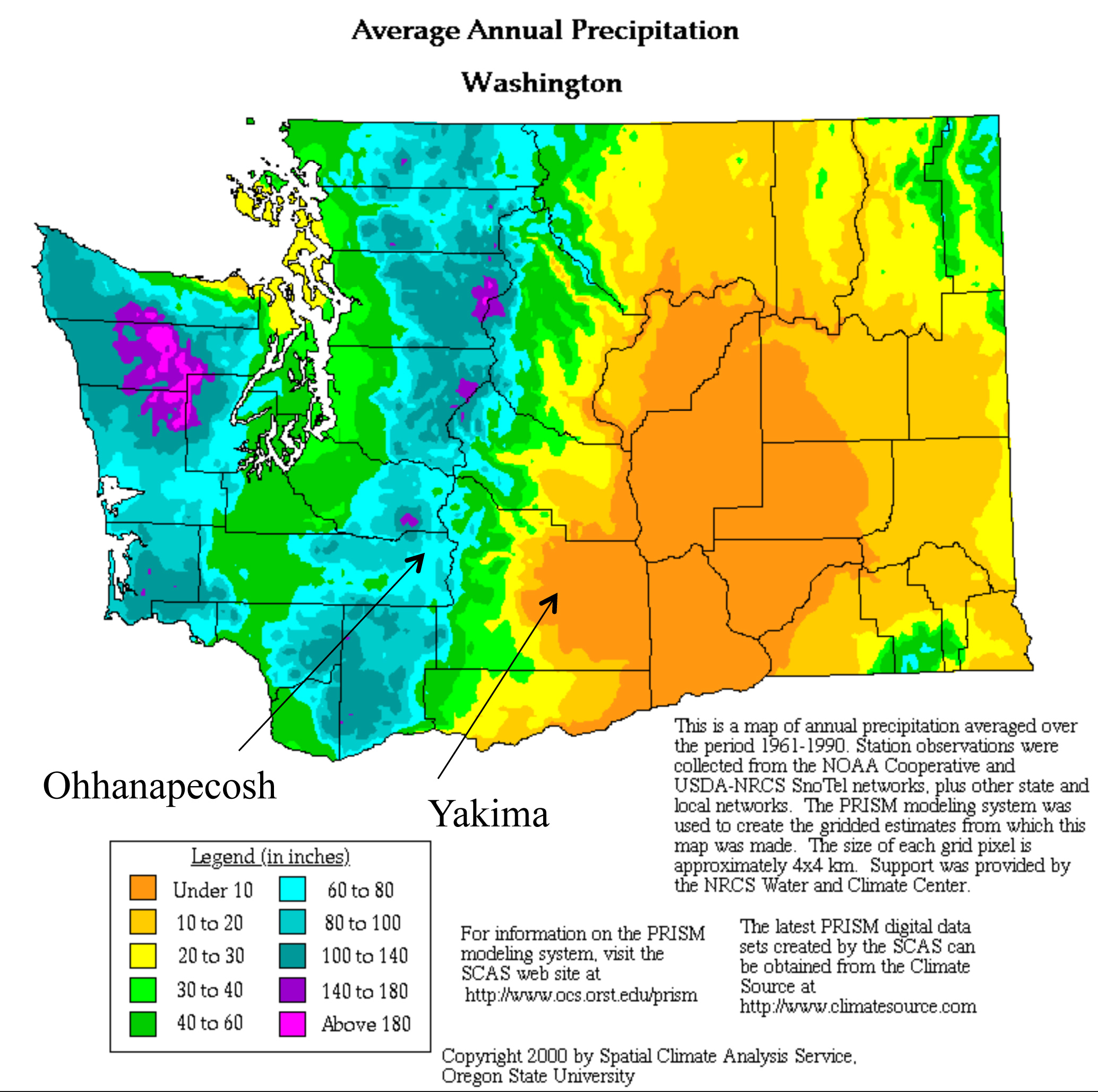

The William O. Douglas Trail, over much of its distance, is strongly affected by the Cascade Mountains rain-shadow. The west slopes of these mountains are drenched with copious precipitation from Pacific storms. Much of the moisture from these storms is wrung from the clouds on the western slopes. Precipitation declines dramatically on the east slopes. While about 100 inches per year falls on the crest in this region, only 20 miles east, less than 25 inches is recorded. A further 20 miles east, Yakima receives only 8 inches of precipitation per year – mostly during the winter season.

The William O. Douglas Trail follows a transect along a route from warm and dry at the base of the Cascades in Yakima upwards through progressively colder and wetter slopes of the Cascades, passing through three recognized ecoregions. An Ecoregion encompasses broad, connected landscapes containing a distinctive distribution of plant and animal species, with similar ecological patterns and relationships between species and their physical environment. The trail begins near the west margin of the semi-arid Columbia Plateau Ecoregion, and proceeds west and up in elevation into East Cascades Ecoregion. From the crest of this mountain chain, the trail descends the west slopes into the West Cascades Ecoregion.

Within the three ecoregions, pronounced moisture and temperature gradients are encountered along this east-to-west transect. These variations have resulted in a complex mosaic of distinct ecosystems. An Ecosystem is a biological community of interacting species, plus all of the abiotic factors influencing that community, sharing similar ecological processes, substrates, and/or environmental gradients. Within this broad framework, at a finer scale, plant ecologists identify a multitude of communities. In all, 13 distinct Ecosystems are encountered along the William O. Douglas Trail, from desert-like shrub-steppe near Yakima to the super-wet temperate rain forest at Ohanapecosh in Mt. Rainier National Park. Between, the William O. Douglas Trail landscape is mantled in an impressive diversity of forested ecosystems, from dry forest to wet forest types and non-forested ecosystems, from wetlands to shrublands to alpine parklands These ecosystems showcase the region’s extraordinary biodiversity, virtually unsurpassed anywhere in North America over such a limited distance.

What follows is an outline of the natural features found along the William O. Douglas Trail from its beginnings in Yakima to its end in Mt. Rainier National Park. Ecosystems are bolded below.

Riparian. The trail begins in an urban setting in downtown Yakima, a thoroughly altered landscape in the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion. Soon the trail joins the Yakima Area Greenway along the Naches River and encounters some native cottonwoods and willows and man-made lakes, old gravel borrows. Ospreys nest here and various waterfowl frequent these ponds in spring and fall.

The trail abruptly leaves the urban landscape and traverses increasingly wild and pristine conditions along Cowiche Creek. Here the trail enters Cowiche Canyon Conservancy. For its location on the edge of a major urban area, the the riparian ecosystem along this section of Cowiche Canyon is remarkably pristine. Diversity of flora and fauna, and aquatic species along this trail has been much-studied and catalogued, serving as an important recreational and educational resource for residents of the region. Over-arching streamside shrubs such as red-osier dogwood provide critical habitat for the Lucia Azure, a rare butterfly. Shaded streamside vegetation provides critical cover for spawning coho salmon in the rushing creek. Federally threatened anadromous Steelhead use Cowiche Creek. Colorful migrant birds inhabiting the riparian zone include yellow-breasted chat, Bullock’s oriole, and lazuli bunting in addition to the more modestly attired residents such as black-capped chickadee.

Shrub-steppe. Uplands in Cowiche Canyon are grown to a mosaic of shrub-steppe plant communities, the classic Great Basin ecosystem, Deeper soils are dominated by big sagebrush and tall bunchgrass. Shallower soils (lithosols) have dwarfish shrubs such as rigid sagebrush and various buckwheats. These are enlivened with a colorful wildflower display, comprised of many species, in spring. The diversity of biscuitroots is noteworthy, with at least seven species present. This group of plants were important in the region’s cultural history as a carbohydrate-rich food for the Yakama Tribes.

Flanking the shrub-steppe are basalt and andesite cliffs, a common feature on the Columbia Plateau. These lichen and moss encrusted cliffs provide nesting habitat for various raptors, and both canyon and rock wrens. Pacific rattlesnakes, docile unless threatened, are often encountered by hikers, especially on warm spring days. Piercing whistles from yellow-bellied marmots sunning on outcrops are often heard by hikers, too.

West, the trail climbs out of Cowiche Canyon and crosses Summitview Road, briefly skirting the ever-expanding Yakima urban area and ascends Cowiche Mountain. A steady climb to the east summit of Cowiche Mountain traverses big sagebrush and bluebunch wheatgrass, core habitat for Washington state threatened Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Thrasher, both bird species dependent on high quality shrub-steppe. These areas of deeper soils alternate with lithosols where the rare plant, Tauschia hooveri, and an abundance of biscuitroots, occur on gravelly, thin soils. The Columbian Lomatium, very near its northern limit, produces an exquisite pink bloom in spring on talus slopes. Many other species of wildflowers enliven the shrub-steppe in spring, creating a floral display attracting many admirers.

Three miles west of Summitview Road, the trail enters Snow Mountain Ranch, a preserve of the Cowiche Canyon Conservancy (summit elev. 2,968’). On the mountain’s north side, in areas with delayed snowmelt another shrub-steppe association, the three-tip sagebrush and Idaho fescue, occurs. This habitat is home to Townsend’s ground squirrel, a rare and declining species.

Garry Oak. Descending to Cowiche Creek (South Fork), a significant grove of Garry Oaks is encountered, alternating with Riparian Zone elements. The oak groves here are some of the northernmost on the Cascade Mountain east slopes and are home to Lewis’s woodpeckers and western scrub-jays, both strongly associated with oaks. The western gray squirrel, a Washington state threatened species, and closely associated with oaks, finds habitat here.

North from Cowiche Creek, south-facing slopes are mantled in a shrub-steppe community dominated by scattered bitterbrush. This habitat provides prime winter forage for the large mule deer population that migrates seasonally up and down the east slopes of the Cascade Mountains. Turkey vultures and golden eagles frequent this zone, too combing the slopes for carcasses of both mule deer and elk.

Traveling west, along and up East Divide Ridge, various draws on the undulating terrain are grown to a remarkable mosaic of vegetation tied to two ecoregions: the upper Columbia Plateau (shrub-steppe) and lower East Cascades (various dry forest ecosystems).

Ponderosa Pine. Ponderosa pine forest is the first “dry forest” ecosystem encountered on the WOD Trail. Over many areas in western North America, dry forests dominated by ponderosa pine form the “lower timberline,” as one increases in elevation and moisture from treeless ecosystems at lower elevations. In Washington, the ponderosa pine zone typically begins on sites with at least 14 inches of precipitation. Characteristic bird species include white-headed woodpecker, pygmy nuthatch, western bluebird, and Cassin’s finch. Mammals include the rare western gray squirrel.

The mosaic of vegetation zones along the William O. Douglas Trail on East Divide Ridge makes this area a “hotspot” of biodiversity. Several credible studies, including the Washington GAP Analysis and another by the University of Montana, conclude and emphasize that the lower east slopes region of the Cascades, because of their mosaic of vegetation zones found in proximity, harbor a very high number of species of flora and fauna. Plant lovers, butterfly fanciers, and birders certainly recognize this region as hosting an impressive list of their favorite group of species.

Interior Douglas-fir. Upward on Divide Ridge, precipitation increases to a level favorable for growth of Douglas-fir. The variety of this fir on the Cascade Mountain east slopes is sufficiently different from the much larger Coastal Douglas-firs of the Cascade Mountain west slopes that it is named “Interior Douglas-fir.” Shrubs such as snowberry and ocean spray become common. Birds include sooty grouse, pileated woodpecker, Cassin’s vireo, and dark-eyed Junco.

Grand Fir. Still upward in elevation and westerly on Divide Ridge, precipitation and especially snowfall increases markedly from the Ponderosa Pine Zone. Grand fir becomes dominant, with western larch and a mixture of other conifers. Some call this the “mixed-conifer” zone on account of its high diversity of conifers (firs, pines, larches, hemlocks, and spruces). This is the “Kingdom of the Woodpeckers.” No less than 10 of 13 Washington woodpecker species can be found in this zone, making the WOD Trail among the very best sites in the United States for diversity of this group. This is also core habitat for the endangered Northern Spotted Owl. Northern flying squirrel is a characteristic mammal.

Subalpine Fir. Uppermost elevations near Jumpoff Lookout (elev. 5,670’) are characterized by cold and snowy winters, favoring subalpine fir and whitebark pine, both typical tree species of boreal (northern) habitats. Squawking Clark’s nutcrackers and the ethereal song of the hermit thrush are characteristic here.

Pond, marsh, and streamside communities. Down into the Tieton Basin, the WOD Trail trends west through dry forests of both the Grand Fir and Ponderosa Pine Zones and winds around various high elevation wetlands, some the result of numerous landslides sloughing off Divide Ridge to the south during the recent geologic past. These are species-rich wetlands, lending impressive biodiversity in the dry forest landscape. Adjacent to some of these wetland sites are extensive alder thickets, alive with Neotropical warblers, vireos, tanagers, and flycatchers in the warmer months. In October, Clear Creek is packed with tens of thousands of kokanee salmon, a small species of land-locked salmon. Bald eagles, American dippers, and common mergansers congregate to feast on fish eggs and carcasses of these fish. Nearby, Clear Lake provides important waterfowl habitat for nesting Barrow’s Goldeneyes and Ring-necked Ducks. In both spring and fall migration it provides an important resting and refueling stop for many other waterfowl and other types of waterbirds. Trumpeter Swans winter in small numbers in areas of the lake that remain open.

Interior Western Hemlock Zone.On shaded slopes beginning near the west end of Rimrock and Clear Lakes, a transition from dry to wet forests is occurs. Stands of western hemlock occur, a dominant tree west of the Cascades. Among the hemlock trees, especially along stream courses, the presence of western red-cedar is a further hint one is approaching the Cascade crest and a westside flora. Tree, shrub, and forb components in this forest are somewhat different than those on the west slopes of the Cascades, hence “interior,” akin to the same forest several hundred miles to the east in the Selkirk Mountains and north into Canada, the “Interior West Belt.” Chestnut-backed chickadee, golden-crowned kinglet, and varied thrush are common birds.

Crossing US-12 along Indian Creek, and then climbing northwest on Sand Ridge, the trail enters the William O. Douglas Wilderness Area, an expansive 168,000-acre wildland commemorating the trail’s namesake. The Subalpine Fir ecosystem is again entered, and the trail is in this ecosystem to near the Cascade Mountain crest. This forest is very snowy and cold, with a short and cool summer. It is a boreal (northern) zone with open forests dominated by the spire-shaped subalpine fir. Interspersed with the tree clumps are scenic mountain lakes and ponds. With increasing elevation, the forest becomes less continuous and more stunted, and a low shrub (huckleberries and mountain ash especially) layer becomes conspicuous. This is a landscape with seven or more months of winter snow cover, a very rigorous climate, indeed. Gray jays, or “whiskeyjacks,” are characteristic birds of these high elevation forests, excessively snowy in the winter and excessively buggy in summer. Mountain chickadee, hermit thrush, and gray jay are other characteristic birds, while typical mammals include pine marten, red squirrel, and boreal redback vole.

Mountain Hemlock. At the Cascade Mountain crest, the trail, as it begins to descend, enters the third ecoregion: the West Cascades. At this point, winter reigns for at least eight months with a stupendous snowpack, indeed the highest recorded anywhere on earth. The total winter snowpack typically exceeds 600 inches per year and nearby sites in this ecosystem, (Paradise and Mt. Baker), have recorded a world record 1200 inches in one year, just over 100 feet! In this ecosystem of deep and persistent snowpack, subalpine fir is replaced by mountain hemlock. This “snow forest” is found along the west slopes of the Western Cordillera from southeast Alaska to about Crater Lake in Oregon. Mountain hemlock is the dominant tree, a species wedded to wet, cold feet throughout the year. Typical bird species include gray jay and dark-eyed junco.

Alpine Parkland.As snow depth and duration increase, the growing season shortens and forest cover diminishes. Trees become ever more dwarfed, creating a parkland of picturesque tree clumps alternating with meadow or heather openings. The driest aspects of these openings are covered with a dwarf shrub cover (huckleberries, heathers or mountain ash). Wetter areas are mantled in lush herbaceous meadows. In July and August, after the deep winter snows finally melt, these meadows burst into a wildflower show of international fame, attracting visitors from afar to hike, photograph, and simply view this wildflower extravaganza set amidst rugged, picture perfect peaks of the high Cascades. Characteristic birds include the Clark’s nutcracker. The most conspicuous mammal is the hoary marmot, whose piercing whistles warn of a predator such as an eagle passing over. Elk and mule deer graze and browse this landscape from summer to first snowfall.

Silver Fir. Descending west towards Ohanapecosh, along Laughingwater Creek, as snowpack decreases, mountain hemlock thins and is replaced by a magnificent silver fir forest (well-named Abies amabilis, Latin, one meaning is lovely). Birds and mammal life are not diverse in this forest. Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Golden-crowned Kinglet, Pileated Woodpecker, and Varied Thrush are characteristic birds while Douglas squirrel is a common mammal.

Western Hemlock. Down in elevation, silver fir gradually thins out, replaced by western hemlock. Douglas-fir is the pioneer tree species in this quintessential “wetside” forest zone, gradually replaced by hemlocks over time, a shade tolerant species. As with the Silver Fir Zone, bird and mammal life is neither diverse nor abundant. Chestnut-backed Chickadee, Pacific Wren, Golden-crowned Kinglet, and Pileated Woodpecker are characteristic birds while Douglas squirrel is a common mammal.

Near the trail’s terminus, at Ohanapecosh is an old growth temperate conifer forest of towering Douglas-fir, western hemlock, and western red-cedar. “Grove of the Patriarchs.” is indeed fitting. Few who walk through this trail are not moved spiritually. This colossal forest is indeed a fitting end for the William O. Douglas Trail, named in honor of an individual who celebrated wilderness and worked tirelessly to preserve natural wonders such as this across the United States.

Nomenclature for forested and shrub-steppe ecosystems follows:

Cassidy, K.M. 1997. Land Cover of Washington State: Description and management. Vol. 1 in Washington State Gap Analysis Project Final Report. WA Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, University of Washington.

For the wetland ecosystem: Johnson, D.H., and T.A. O’Neil. 2001. Wildlife-Habitat Relationships in Oregon and Washington. Oregon State University.

Andy Stepniewski

March 2012