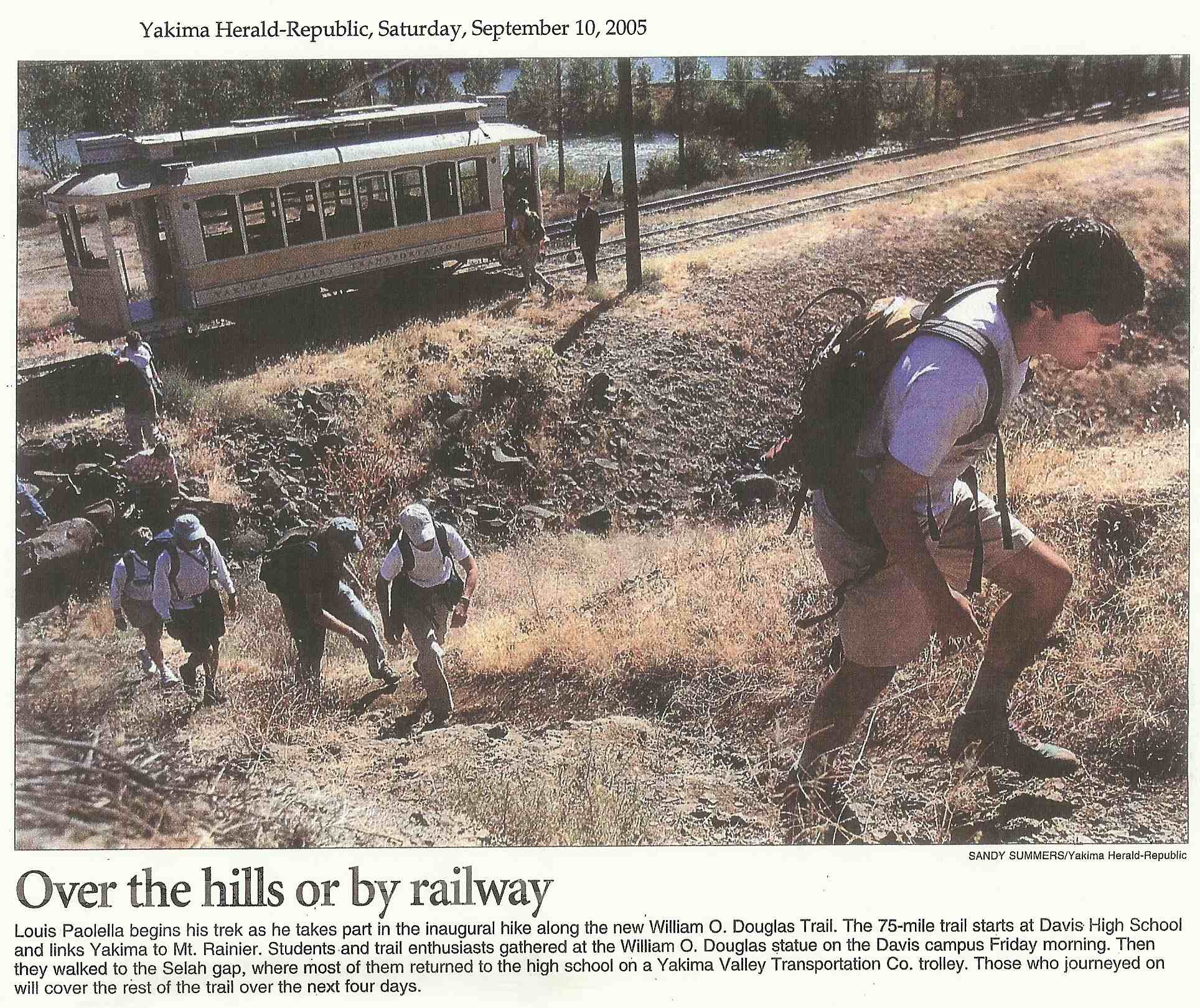

Selah Gap Hillclimb

William O. Douglas was 5 years old when his father died in 1904. Also struggling from a bout with infantile paralysis, Douglas was left greatly weakend during childhood. In 1910 he decided to strengthen his legs by hiking north from his 5th Avenue house in Yakima, along North 6th Avenue to the Naches River bridge and then up into the hills near Selah Gap. Douglas describes his condition in the book Go East, Young Man,

By boyhood standards, I was still a cripple, unable to compete physically. . . . I was a failure. If I were to have happiness and success, I must get strong. And so I searched for ways and means to do it. I got myself a set of barbells and practiced day after day, trying to strengthen my legs, back, and arm muscles. Even so, strenuous exercise still made me feel faint. Sometimes I would vomit, sometimes I’d get a severe headache. So I decided to start hiking the sagebrush hills that rim Yakima.

Thus I started my treks, and used the foothills as one uses weights or bars in a gymnasium. First I tried to go up them without stopping. When I conquered that, I tried to go up without a change of pace. When that was achieved, I practiced going up not only without a change of pace but whistling as I went.

I always went alone. The hills to the north of Yakima were only about two miles away. I often crossed the [Naches] River on the Northern Pacific Railroad bridge (where later I was to spend much time with hoboes and Wobblies) and then went up the hill.

That fall and winter the exercise began to work a transformation in me. By the time the next spring arrived, I had found new confidence in myself. My legs were filling out. They were getting stronger. I could go the two miles to Selah Gap at a fast pace and often reach the top of the ridge without losing a step or reducing my speed.

My heart filled with joy, for I knew I could accept the invitation [to get acquainted with the mountains]. I would have legs and lungs equal to it.

My love of the mountains, my interest in conservation, my longing for the wilderness - all these were lifetime concerns that were established in my boyhood in the hills around Yakima and in the mountains to the west of it.

It was at Father’s funeral that Mount Adams made its deepest early impression on me. Indeed, that day it became a symbol of great importance. . . . I happened to see Mount Adams towering over us on the west. It was dark purple and white in the August day and its shoulders of basalt were heavy with glacial snow. As I looked, I stopped sobbing. My eyes dried. Adams stood cool and calm, unperturbed by the event that had stirred us so deeply. Suddenly the mountain seemed to be a friend, a force for me to tie to, a symbol of stability and strength.

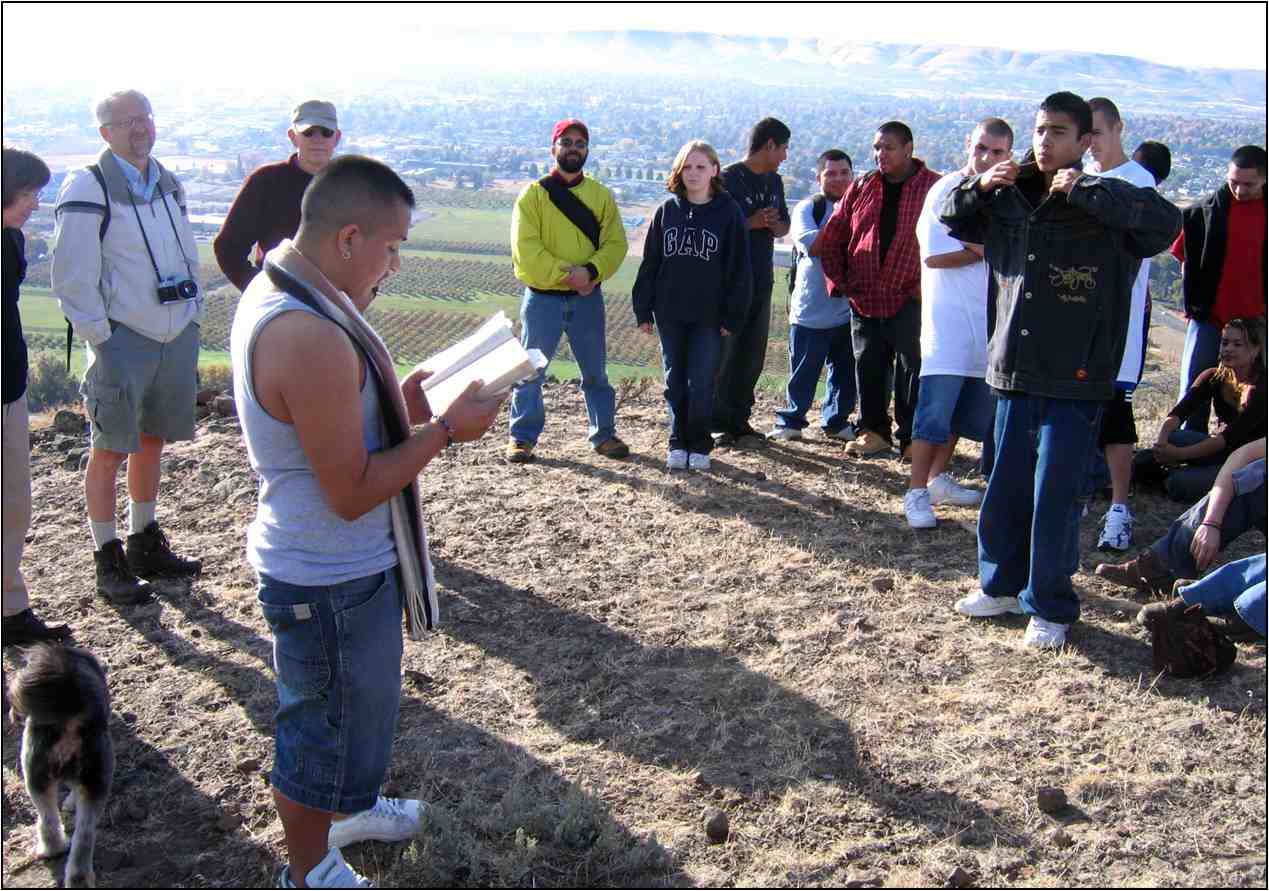

Davis High School students reading passages from Go East, Young Man: